From Nepal to Dhaka

My seat was in an emergency exit row, and when we took off a tiny bit of turbulence made the plastic cover of the emergency door handle fall in my lap. I locked eyes with my neighbour and we both...

This is the third story I wrote recounting my experience moving from Amsterdam to Asia in 2015. After reading 'The Money Trap' I felt suddenly inspired to write in a more story/novel type of format. This period in my life was super eventful, and I’ve often looked back at the photos and recounted these stories in person. After the events retold below, I moved to Myanmar. I might write one more story about my time there, but it feels less condensed. I was there for much longer, so there were a lot more random Tuesdays. Not to say that nothing funny happened. In fact Myanmar was an absolutely hilariously difficult environment to build businesses and just generally live, but it was a lot less intense than Dhaka. Some of the other expats in Myanmar would get really annoyed by cars honking. Me and a few others who had spent time in Dhaka said: “Wait? What honking?” To us, it was nothing.

The flight from Kathmandu to Dhaka

This time, I had double-checked the date when I booked the flight. Check-in for our Biman Bangladesh Airlines flight to Dhaka went smoothly. My Dutch intern who was supposed to join me in Nepal for 6 months had arrived two days ago. Like me, he'd heard less than two weeks earlier that it was going to be Bangladesh.

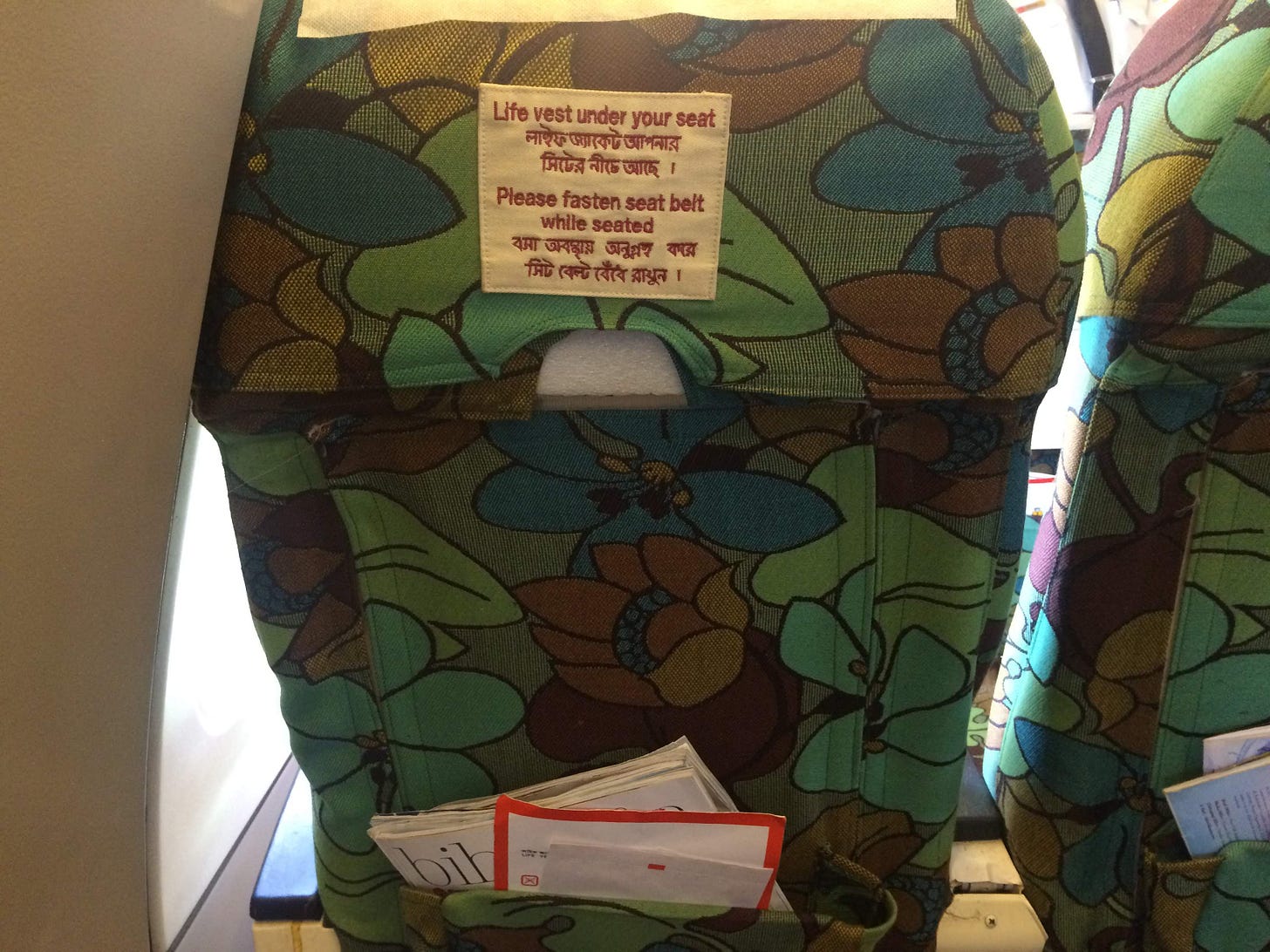

The moment we stepped onto the plane, it felt like time had frozen sometime in the 1970s. The seats sagged with worn-out, flower pattern upholstery, and as luck would have it, I ended up in the emergency exit row. As we took off, a small jolt of turbulence sent the plastic cover of the emergency door handle falling right into my lap. My neighbor and I locked eyes, both of us sharing a silent, mutual panic before we erupted into laughter. I carefully clicked the cover back in place, and thankfully it stayed put after that.

The plane was so old that it had a communal big screen at the front of the cabin instead of small personal entertainment systems. What started playing on the screen, of all things, was Mr. Bean. And then, as if to top off the surreal experience, the cabin crew handed out the “meal”: a dry bread roll and two packets of ketchup. I scanned the faces around me, expecting disbelief, but everyone seemed unfazed. My neighbor opened his roll, squeezed some ketchup on it, and munched away, enjoying Mr. Bean’s antics. I joined in on the laughter, wondering what else Bangladesh had in store for us.

When the plane approached the tongue twisting Hasret Shahjalal International Airport in Dhaka, I pensively looked out the window as our plane descended into a thick blanket of brown haze. This was smog. I had been in Kathmandu during a time when the air in Kathmandu is relatively clean, but that would not be the case in Dhaka. Never had I seen air pollution this bad. It looked disgusting and my first instinct was to hold my breath as I saw the plane being fully engulfed by the smog. Then again, I still smoked back then, so I figured worrying about the air would be a bit hypocritical.

A most surreal show of bureaucracy

After landing, my intern and I walked through the terminal and looked at each other, impressed. This airport was much more advanced than Kathmandu! That could not be said about the Visa counter however. That first time, we got in quickly, as would usually be the case. But during one later time I was lucky enough to witness what is probably still the funniest bureaucratic process I have ever seen in my life. The immigration officer sat behind an enormous, ancient book—think Harry Potter-sized. He wrote each traveler’s information by hand into the book, stamped a form, and handed over a paper visa. It was almost efficient—until the page filled up. What followed was a bureaucratic masterclass: the officer calmly flipped to a fresh, unlined page. Then, without missing a beat, he pulled out a ruler and pencil and started drawing new lines. The queue groaned audibly. It took a solid five minutes of silent disbelief before he finished, waved the next person forward, and carried on like nothing happened. It was hard to contain my laughter.

Dhaka

Now, in contrast to Kathmandu, Dhaka is not safe. It is certainly not anywhere near as dangerous as Caracas or Lagos, but you don't want to wander into the wrong neighbourhood by yourself. The stories in the local English newspaper were shocking. Almost every day there would be someone hacked to pieces with a machete. That seemed to be the weapon of choice for murders in Dhaka. Therefore, we got a taxi in favor of the local Tuk Tuks, locally known as 'CNGs' or 'Cages of Death' (we probably made that up). There were stories that during civil unrests, one horrible way to die was when someone would lock the CNG's metal cage from the outside with a metal lock and then throw a molotov cocktail into the cage. At the time, there was some significant civil unrest going on. Luckily, as foreigners we were left completely out of this. Expats joked that if a prospective molotov cocktail thrower saw a foreigner passing by, he would wait until the foreigners were out of sight before lighting the fuse. Still, one did not want to make a serious wrong turn in Dhaka.

It's hard to explain the fondness I feel for Dhaka, and for Bangladesh in general. I ended up only living there for 4 months, and coming back for about 2 weeks each quarter in the 2 years after that. As unlikely a place it was to have one of the most fun times of my life, that's what happened. We were immediately adopted by the teams of the few other Rocket Internet ventures that operated in Bangladesh. The first weeks we worked from one of the other company's offices, and after that we got an office just a few blocks away.

The people of Bangladesh were wonderfully enthusiastic—always eager to teach us about their culture, but nearly incapable of giving a straight answer. Every meeting felt warm and productive, but follow-ups? A different story.

As foreigners, the privilege we enjoyed was almost surreal. Some of my colleagues met Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus, apparently just by asking. I somehow ended up on a local talk show with seven million viewers, and we were already discussing a Bangladeshi version of The Apprentice, where I’d be one of the judges. One Rocket colleague even moonlighted as a model, with his face plastered on billboards around the city.

We took full advantage of this bizarre privilege. A colleague once walked into a restaurant kitchen to teach the staff how to make coffee. Another reset a “broken” credit card machine himself. I even drove a CNG back to our apartment one night—driver in the back, laughing hysterically. It was a natural escalation from our usual game: convincing rickshaw drivers to let us pedal their bikes home. It was illegal to electrify a riksha, but many who could afford to do so understandably did it anyway. I became adept at spotting the signs: a poorly hidden cable, a thumb switch on the handlebars. Once we hit the final straight on Gulshan Avenue I would kick in the electric motor and leave my friends in the dust.

The Korean Rooftop (that's not what it was called, but that's what we called it) was one of our main after-work watering holes. It was on the top floor of a decrepit building that might have once been a hotel or condominium. There was an empty swimming pool, the lights still working for the vibes. Once or twice the staff put a table inside the pool for us if the restaurant was full, which meant we had to get in and out using the pool stairs, and our food and drinks orders had to be handed down into the pool from the side. The manager, Masum Bhai (bhai means brother), was always ready to help us drink enough Hunter beer and Soju to forget the smog and the stress of trying to build tech startups in that absurd environment. He often let us stay until well past closing time. There was a tantalising metal stairwell that led up to an even higher roof. Every visit involved the same ritual: begging Masum to let us explore this mysterious higher rooftop. He refused every time—until my farewell party, when he finally gave in. We ascended triumphantly, beer in hand, to survey the smoky sprawl of Dhaka from this rooftop garden.

Rainy season

One evening there was a massive storm. I was still in the office when the floor to ceiling windows (one reason I picked the place) started moving and bowing so aggressively that I was sure they could shatter any moment. With no better option, I decided to open the windows a crack, hoping to let the wind pass through and relieve some of the pressure. It worked, but at the cost of a soaked office. Rain gushed inside, covering the floor in puddles. The next morning, we heard the news: a man had been killed by a flying billboard during the storm. I remember thinking, What a ridiculous way to go.

A scary lunch spot

Another time, I had gone to lunch with a few others on the 12th floor of a new'ish building across the street. When I asked where the bathroom was, the waiter pointed at a door. The moment I opened the door, I was hit by blinding sunlight. I took a step forward, only to realize I was standing outside. My brain took a moment to register: there were no walls or windows, just an open void. A few meters ahead of me, the floor ended abruptly, and beyond that—nothing but a dizzying twelve-story drop. The door to the actual toilet was a few steps in the other direction. I quickly went in, peed, and walked back out, trying not to look down. When I told the others, they naturally had to see it for themselves. They came back, wide-eyed, muttering, "Yeah, we’re never eating here again." Another day, I randomly got hit by a car from behind when walking to lunch. Thankfully the car hit my left leg while my weight was on the right leg, so I was unharmed. But, wtf?

Traffic in Dhaka reached a level of absurdity I never thought possible. It once took me two hours to travel five kilometers. One day, our car got stuck at an intersection where vehicles from all four directions had inched forward until they were nose-to-nose, completely blocking each other. Nobody moved. A couple of traffic officers stood off to the side, holding green and red batons, but they seemed just as helpless as the drivers. My colleague and wanted to get home. We got out of the car, borrowed the officers’ batons, and took control of the intersection. What happened next was surreal. As if by magic (and probably our white faces again), everyone followed our instructions. We backed up cars, gestured wildly, and shouted instructions in broken Bangla. The drivers bemusedly followed our lead, and within minutes, we had cleared the jam. I still laugh when I think about the sight we must have made: two tall foreigners in business casual jumping around, waving traffic batons and shouting at the drivers. It must have made the rounds at dinner tables across Dhaka that night. We got back in our car and carried on. Shame no pictures were taken (not by us in any case).

There were a couple of expat clubs in Dhaka. They were pretty nice, with a pool, western food, beer, and parties. We never really felt like we belonged with the non-Rocket expats though. Most of them were working either in the garments industry, or at NGOs. A lot of them openly despised their job and the fact that they were in Dhaka, which we didn’t really get. Of course, a healthy dose of dark humour (and functional alcoholism) was welcomed, not to mention practiced by us as well. But if you really, genuinely hate your job, why stay? Quite a few of them also used a worrying amount of prescription drugs. One day, when I walked into a pharmacy for some painkillers they asked me if I wanted anything else, something stronger perhaps? I asked what they had. “Oxys, Xanax, Ritalin, whatever you want!” The Xanax was nice for flights, and the occasional after work wind down, but I’ve seen some of the garments folks get themselves into dark places, especially with the opiates. The NGO people were not much more relatable. Their lives were spent living in a gated community, going to expat clubs, and traveling by white Toyota Landcruiser to the poorest parts of the country to do their jobs. From their perspective, Bangladesh was a contradictory place with nothing but abject poverty and suffering on the one hand, and gated communities for the wealthy. We, on the other hand hired 20 year old fresh graduates from the local universities. They just wanted to make money, get married, and have fun. To us, the country appeared a lot more normal, with young, hard working people not very different from young, hard working people anywhere else.

By no means do I mean to gloss over the real poverty on display daily. It is quite crazy to see what happens when labour is that cheap. The immigrations officer drawing lines by hand is one example, but one of the most absurd things we saw everywhere we went was men breaking up fresh bricks with little hammers. So bricks were made somewhere, transported into the city, where they were then turned into gravel one by one to pave roads.

Smog revisited and a trip

After about a week in Dhaka, I made the mistake to go for a run in the park. When I got back, I was coughing and heaving from running in such thick smog. I pulled a piece of black muck out of my nose. Never again. That was probably what gave me the inner ear infection that came on about a week later. One of my ears stopped working well, and it got so bad that when I tried to clear it, I actually had to sit down on the floor because I got dizzy. We had planned a trip that weekend to a remote island on the other side of the Country, called St. Martins. Feeling a bit worried about this vertigo episode, I almost cancelled. But then I decided that a couple of days away from Dhaka on a tropical island would probably be exactly what I needed. It was. On the second day I went snorkeling and after diving down to the bottom and equalizing the pressure in my ears (no vertigo this time), I came back up and felt a whole stream of crap drain out of my sinuses. That felt so much better. I never went running in Dhaka again, and I've never had vertigo since.

Our trip to St. Martin’s Island began with an overnight bus ride along one of the most dangerous roads I’ve ever traveled. The road itself was smooth asphalt, but it had no guardrails, no lane markers, and no streetlights. As the story went, international NGOs—including the World Bank—had funded the road's construction, but the budget for safety features mysteriously evaporated somewhere along the way. The result? A sleek but deadly highway, littered with the remains of wrecked cars and smashed CNGs. It was unsettling, especially when our female travel companion confessed that someone had groped her while she slept. One of the guys in our group wasn’t having it—he dragged the offender out of the bus at the next stop and gave him a couple of solid bitch slaps to the face. For a moment, it felt like the situation could escalate into something ugly, but to our relief, it didn’t. Everyone seemed to agree that justice had been served. The offender was moved to a seat in the back, far from the rest of us. The incident was over, just like that, as if the slapping had reset the balance.

Stories of Myanmar

When we got on the boat in Teknaf the next morning, nobody had slept much. We were relieved to be out of the bus, on a boat with space to walk around, and last but not least, clean air. As the boat headed south to St Martin's Island, the Myanmar coast lay just off our left side. One of our friends had spend a couple of months in Myanmar and regaled us with hilarious stories of a place that seemed even crazier than Bangladesh. He recounted how on one weekend trip to the shore, they had ordered a grilled fish. When the fish arrived charred on the outside and still completely raw on the inside they tried to show the staff that it needed to go back on the grill. What unfolded was a slap stick comedy show of the waiters all passing the fish around as if it was a ticking time bomb. When finally someone had no choice but to try and solve whatever the problem was, he took it back to the kitchen. They must have next discussed among themselves what these white people could possibly want. After some time, the fish came back. Still raw, but now covered with mayonnaise. Apparently, the conclusion was that white people like mayonnaise, so that would probably solve the issue. It made you wonder, had they ever cooked fish before? Was eating fish like that a local specialty? (it wasn't). He also told us how in Myanmar people mix a couple of empty plastic bottles into the frying oil, to make the fries crispier. That one seemed fantastical, but it would turn out to be an extremely persistent rumour. Worryingly persistent, actually. In any case, I thought it sounded like an amazing place and I hoped I would have the chance to visit and check it out for myself.

The earthquakes

Later, on a Saturday morning, I was having coffee at Holy Bakery when suddenly, everyone fell quiet. It felt as if the world was turning the wrong way, and I thought to myself "woah, this is a weird hangover...". Then I heard a woman shout: "Earthquake!" We learned that Nepal had been hit very badly by a massive earthquake. Not only was I originally supposed to be there, after texting some people I knew exactly where I would have been. My friends there were at a poolside gathering, and they relayed the story how the water was sloshing out of the pool. They were all fine, but others were not so lucky. The earthquake killed 8,962 people and injured 21,952 across Nepal, India, China and Bangladesh. Several aftershocks followed in the next few days. In one utterly absurd moment, an earthquake hit as we were having a meeting in our 7th floor office. One of the Germans stood up and shouted, as the water sloshed around in the watercooler: "Let's continue ze meeting! If you zstand up you hardly notice it!!" The rest of us were already halfway down the stairs.

Goodbye Dhaka

Dhaka was chaotic, unpredictable, and full of contradictions. It could be exhausting, but left me with stories I’ll carry for the rest of my life. But more than that, it surprised me with moments of joy and camaraderie, not to mention the amazing food.

Whether I was nearly falling off a building, directing traffic, or getting hit by a car, Dhaka had a way of turning every experience into an adventure. And somehow, amidst the smog and the madness, it became one of the most unforgettable chapters of my life. I was moving to Myanmar, and that would be it’s own much longer, incredible chapter.