Bootstrapping life from a cosmic hotpot under a cyanide sky to turbine powered monsters

Did you know you have tens of trillions of tiny electric turbines in your body that spin at up to 21,000 RPM? A lesson in physics, chemistry, biology and the origins of life.

The Microbiome post was quite popular, and I personally enjoyed revisiting some of the topics of my Bachelor degree. As usual, I went a little too deep down the rabbit hole, and ended up tracing back how metabolism and life itself works all the way to the origin. I will now attempt to summarize what we know about the origin of life, how life’s (ancient) fundamental machinery works, and hopefully strengthen the foundations under the microbiome understanding (and more).

Everything is thermodynamics

It’s no wonder that tech bros and rationalists obsessed with ‘first principles’ are fond of talking about ‘entropy’ (even in business settings). Thermodynamics really is the foundation of everything that relates to energy. There are two key laws of thermodynamics that matter here:

Energy cannot be created or destroyed, only converted

Entropy always increases

The first one is straightforward. If you burn a match, the energy stored in the wood is released in the form of heat. The match is used up, but the energy lives on, dissipating into the universe. Likewise, to create a match, we must use some other form of energy: burn glucose in muscles to move a saw, for example. This also generates heat, which our bodies radiate out into the universe.

The second law is a lot harder to explain. But unfortunately we really need it to understand everything else. Let’s try this first: In the absence of constant effort, everything turns to dust and heat. Or think about this: Imagine you have a deck of playing cards, fresh out of the box ordered Ace to King. You throw the cards into the air. What is the chance of them landing perfectly sorted in a stack? Near zero percent. There are billions of ways for the cards to land, and only one ‘correct’ way. This is also why headphone cables always get tangled up. Why a one year old can’t eat yoghurt without turning itself into a yoghurt monster. Everything trends to chaos naturally unless we put energy into preventing it.

To bring that back to energy and heat. Energy always flows from organized to dispersed. Heat flows from hot coffee into the room around it. You cannot unboil an egg or reconstitute a log of wood from a pile of ash. On the other hand, a log of wood contains energy. Energy is ‘trapped’ inside (for a while) in molecules like cellulose. The second law of thermodynamics pushes for that log to burn and energy to be freed up as heat.

How does energy get freed up? What is this energy? What is ‘burning’? Welcome back to high school chemistry. The situation with the highest possible amount of entropy is the one with the lowest energy, is the one that is easiest to form, is the one that is most stable. In a way, we are just saying that also in chemistry water always flows downhill. Let’s look at burning the simplest fuel, Methane (CH4).

CH 4 + 2 O 2 → CO 2 + 2 H 2O + Heat

This will be the only chemistry reaction I’ll need in this piece. Count the Carbon (C), Oxygen (O) and Hydrogen (H) atoms on both sides of the equation. You’ll see there are equal numbers on both sides. But somehow, the C and the four Hs have all ended up attaching to the Os from Oxygen. This is because an Oxygen is a very powerful electron magnet. Due to its geometry it is short two electrons and really, REALLY wants to get electrons. If we want to answer the next ‘why’ here we’d get into quantum mechanics, and we don’t need to. So let’s move on, knowing that Oxygen is a super powerful magnet for electrons, and will hog and steal them from other molecules whenever it gets the chance. When oxygen forces a molecule apart, it snaps very tightly onto the components, like Carbon and Hydrogen. This tight bond is super stable, and thus low energy. So when CH4 burns with oxygen, less stable (higher energy) compounds get turned into more stable (lower energy) compounds. Entropy increases, so we satisfy the second law. But going from higher to lower energy states means that there is ‘excess’ energy. Because the first law tells us that we cannot destroy energy, that ‘excess’ energy needs to go somewhere. It is in this case simply released as heat (fire is hot). Both laws are satisfied, and if you touch a burning match to a bit of methane in open air you will notice that it does, indeed, burn very well.

These types of reaction with Oxygen are called Redox reactions. The fuel is oxidized while at the same time the Oxygen molecule is ‘reduced’. You cannot have an oxidation without a reduction happening at the same time1. Simply to use fewer words, and because there is no risk of confusion we usually just call these reactions oxidation. So burning is a fast oxidation reaction. Rusting, a slow one. To end this part on a satisfying ‘aha’ note: in your cells, glucose is broken down and the resulting compound, pyruvate, oxidized. This provides the energy for your body to function, but it also generates heat. That’s actually how your body stays warm.

In your life’s never-ending fight against the second law, your body needs to be constantly fed. If you stop eating, your body eventually breaks itself down and you die. This process will satisfy the laws of thermodynamics, but your friends and family…not so much.

If we cannot create energy, and entropy always increases, how can we exist? The answer is simple: because of the sun. We are all solar-powered. Thanks to the massive amount of energy from the sun, nature can assemble molecules like glucose. This doesn’t break the first law because energy is just transformed from one form to another. It also doesn’t break the second law because the sun ‘pays the bill’ for us. The sun sends us concentrated, low-entropy energy in the form of sunlight. Life captures a tiny fraction of that to build and maintain complex structures. The rest radiates into the cold void of space as high-entropy infrared radiation. The books balance because we’re not creating order from nothing; we’re surfing on a river of energy that flows all the way from the ‘Big Bang’ to the cold universe, and entropy increases along the way. The sun itself runs on gravity. When the original gas cloud collapsed into a ball billions of years ago, that gravitational fall is what powered everything. Gravity smashes the hydrogen gas so tightly together that nuclear fusion happens, which pushes back against gravity to slow the collapse down. This allows the the sun to spend its energy budget over billions of years instead of all at once2.

The same type of accounting can be used here on earth. The energy released in a rapid oxidation can be used to boil water into steam and spin a turbine to generate electricity. It is also possible to tap into the energy carried by the electrons moving from one molecule to the other, which is how a battery works. Cells use a process which has strong parallels with the way batteries work, as we will see. We also pay tax to entropy constantly in the form of dissipated heat, sweat and waste from food. After we die, we pay our final debt to the second law and decompose into dust and heat.

From physics to biology

Let’s go from middle school chemistry to middle school biology. We’ll start with plants, which as you surely know can take energy from sunlight to do the seemingly unpossible and ‘unburn’ CO2 and water to produce fuel and oxygen. With some high-tech molecular tricks the plant cells are running the oxidation reaction from right to left, building glucose out of thin air3. The plant then uses that Glucose (a simple sugar) to make cellulose, a complicated carbohydrate. When algae and plants die, over the course of hundreds of thousands of years, various processes slow-cook the cellulose in the absence of oxygen (no oxidation). Fermentation releases initial heat and simplifies the molecules, until deep underground heat and pressure work to form high-energy compounds like oil and coal. Almost all of the energy we use, whether we eat animals, plants or burn kerosene in an airplane is solar energy captured by a plant at some point in history.

To complete our full accounting of energy in the universe, besides captured solar power there are only two other relevant forms of energy available to us: Energy from exploding stars that got locked up as nuclear power in gigantic atoms like uranium, and geothermal energy from the center of the earth. This is ‘leftover’ heat from gravity smashing the planet together, kept hot by the slow decay of radioactive elements deep underground. As for where the energy came from originally? We don’t know. It looks as though the universe appeared out of nowhere in a ‘Big Bang’, with a fixed amount of total energy contained in it. Unless we have missed some very important pieces of the puzzle, eventually all stars will run out of fuel and the universe will gradually cool as it keeps expanding. Entropy should continue to increase until energy is so dispersed that it can no longer do anything at all. The ‘heat-death’ of the universe. The Big Bang is now about 14 billion years ago. The sun formed about 5 billion years ago, and has fuel for another 5 billion. The last star is calculated to burn out 100 trillion years from now.

So now, back to earth. Photosynthesis is critical to complex life, but it was actually only invented about 2.5 billion years ago, whereas life started ~4 billion years ago. It’s time to go all the way back. Life has a number of key universal building blocks. The most fundamental one of them is Adenine. This molecule functions both as one of the four ‘bits’ in DNA code (A, G, C, T) and as the core of life’s metabolic system. ATP (Adenosine TriPhosphate) is the universal energy currency of all living cells. NAD+/NADH (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide) is the cell’s key electron carrier. And Acetyl-CoA (which also contains adenine) carries carbon fuel into the ‘furnace’ to be burned. What is so special about adenine?

Adenosine and the primordial soup

It is now 4 billion years ago, about 500 million years after the earth was formed. It had cooled enough for liquid water to form. The atmosphere was made up of various toxic gasses, including ammonia (NH3) and cyanide (HCN). It just so happens that cyanide reacts easily with ammonia and some heat to form Adenine. Adenine is a remarkably stable compound, even resistant to radiation. So it made sense for nature to use it as a key building block. So, we got Adenine, now we need a molecule to store energy, sugar. Formaldehyde (CH2O) was abundant too on pre-life earth, and it turns out that with some heat it forms sugars. Sugars have two very neat properties that make them critical for life. First, as an energy storage, second, they can polymerize. Sugar molecules can be linked up one after the other to form longer chains. One place where that property got implemented was in RNA (and later DNA) to encode information. RNA is a sugar backbone, with the four bases (Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine and Uracil) attached one to each sugar molecule. The specific sugar used is called Ribose - hence RNA. When you attach Adenine to Ribose, you get Adenosine. That’s one of the ‘chain links’ in RNA (and DNA).

What happened next is not exactly clear, but most scientists think that early life was just RNA. Maybe this is a good place to ask the question what IS life, anyway? There is not one single answer to that question, but one option, just biologically speaking is that life = self-replication. So for scientists studying the origin of life, a key search is for what’s known as 'the first replicator’.

In any case, this step appears to have been the really unlikely one. Adenine, Guanine, the other two bases, as well as sugars like Ribose have been found in meteorites, so we know they have formed all over the universe. But as far as we know, self-replicating life only exists on earth. Along with the questions: What was the big bang and where did it come from? What is dark matter and dark energy? What is consciousness? what exactly was the ‘spark’ that led to the first replicator is one of the key remaining mysteries of science. Although, we do understand this one better than the others.

There are a number of smoking guns in nature that make us believe RNA is likely to be this first replicator. DNA is much more stable than RNA, which was a critical innovation to make complex animals possible, but RNA is actually more versatile. It can not only store information, but it can also directly make unlikely reactions happen, like build longer RNA strands, assemble proteins, and indeed, replicate. Current day ribosomes (which build all proteins in our cells) are RNA based machines. ATP, NAD+, and other ancient molecules all have RNA components (Adenosine). So somewhere between 4 and 3.5 billion years ago, in some warm pond or hydrothermal vent, RNA formed, and figured out how to copy itself. From that moment, evolution could begin. Everything else, DNA, proteins, cells, mitochondria, photosynthesis, animals, your gut microbiome, is based on that first trick. That is also when these building blocks, like Adenosine, were ‘locked in’. Evolution never replaced these or tried something else, because that would in essence mean reinventing life itself.

Cells

A big problem in this early soup was that stuff would kind of just float apart. The eventual solution to this is some very elegant basic chemistry. Lipid (fat) membranes. Lipid molecules are hydrophobic, they hate water. When you put them in water, they spontaneously form little bubbles (vesicles), with a water-fearing wall separating inside from outside.

This wall acts like a force field for charged particles. Protons (H⁺), and ions like Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Cl⁻ cannot pass through unassisted. That turned out to be incredibly useful: early life could now keep its precious molecules close together, and start to control what goes in and out. Phosphorus, in the form of phosphate (PO₄³⁻), is another critical piece. Phosphate groups carry negative charges, so once inside a lipid membrane, they can’t escape. This made phosphorus perfect for building things you want to keep inside: the backbone of RNA and DNA, and the energy-carrying bonds in ATP. The fact that Phosphorus (and Sulfur in Acetyl-CoA) both evolved to have crucial roles in fundamental cell biology also gave scientists another clue about where early life started. Those compounds are associated with volcanoes. That makes underwater ‘geothermal vents’ a strong candidate for the biome where life emerged.

The membrane and its role as a forcefield was a key unlock. With a membrane, life could hack thermodynamics locally. Inside the membrane, a cell can maintain order, keep useful molecules concentrated, and control chemical reactions. Outside, chaos and entropy reign. The cell pays its tax by pumping waste out and radiating heat. But inside its tiny bubble, it builds complexity.

This is still how every cell in your body works today. Your cells maintain ion gradients across their membranes, for example keeping sodium out and potassium in. When a nerve fires, it’s releasing that built-up gradient in a controlled burst. Your mitochondria do something similar - they pump protons across a membrane to store energy, then let them flow back through a turbine (we’ll get to this wild fact soon) to generate ATP. Life is powered by electricity and membranes enable voltage.

The oxygen catastrophe

For the first 1.5 billion years or so, there was almost no free oxygen in the atmosphere. So early life didn’t need it, and in fact oxygen was toxic to early organisms. They extracted energy through fermentation, and many bacteria still can’t survive in air. Then, around 2.4 billion years ago, cyanobacteria figured out a new trick: photosynthesis, which releases oxygen as waste. This was great for the cyanobacteria. For everyone else, it was an apocalypse.

Oxygen is, as we discussed, an aggressive electron thief. It ripped through the existing biosphere, destroying molecules and killing organisms that had no defense against it. This was likely the first mass extinction - and it was caused by life itself. The “Great Oxygenation Event” (or more dramatically, the Oxygen Catastrophe) changed the atmosphere permanently. Even oxygen dependent organisms like us need ways to control oxygen, for example a wide variety of anti-oxidants in the body that sacrifice their electrons to oxygen so it doesn’t destroy something more important. But oxygen’s aggression also makes it incredibly useful for energy extraction. If you could control oxidation instead of being destroyed by it, you could harvest far more energy from food than anaerobic life ever could. To give you a taste for the potential, one glucose molecule yields ~30 ATP when oxidized, while fermentation only yields 2. That’s a 15x difference!

During this period of time, evolution pushed things in two major directions: photosynthesis continued to thrive and plant life exploded, which kept increasing the oxygen concentration in the atmosphere. Secondly, because the resulting oxygen enabled a 15x more efficient metabolic pathway, aerobic life took off.

The key pathway to turn one glucose into so many ATPs is intricate, and involves all those core Adenine based molecules I mentioned before. It happens inside the mitochondria, which is often called ‘the power plant of the cell’. But before we get there, glucose is still too big. So in the ‘main area’ of the cell (the cytoplasm), glucose is split in half to form 2 pyruvate. This part doesn’t need oxygen. The pyruvate is then carried into the Mitochondria, where the real magic happens.

Mitochondria, the power plant

Somewhere around 2 billion years ago, one cell swallowed another, probably trying to eat it. But the engulfed bacterium survived, and both cells found themselves better off. The ‘eaten’ cell was an aerobic bacterium, really good at burning fuel with oxygen, but perhaps not so great at surviving and finding fuel. Inside the larger host, the bacterium got a steady supply of fuel and protection from the outside world. The host got an internal power plant. Over time most of the genome of the engulfed bacterium merged with the host’s and it lost the ability to survive on its own, instead becoming fully a component of the larger whole4. We now know these cellular power plants as mitochondria.

I’m pretty sure you’ve heard of mitochondria, and maybe even heard them referred to as the powerplant or engine. Obviously, those are metaphorical terms people use to make it more relatable, right? Well… no. When people say mitochondria are the ‘engine’ they don’t mean ‘sort of like an engine’. They mean, literally, a rotating electro motor with an axle and everything. This machine is called ATP Synthase, and I find it one of the coolest things you can know about biology.

Embedded in the membrane of your mitochondria are tiny oxidation powered turbines, spinning at jet engine speeds of up to 21,000 RPM. They re-attach a phosphate group to ADP by physically smashing them together to reform ATP. I could hardly believe this when I first heard of it. It’s just too ridiculous. How can this be? How the hell does it work?

The membrane (remember forcefield) is the key. Mitochondria use the energy from oxidiation to pump hydrogen ions across their membrane, creating an imbalance. When those protons flow back through ATP synthase, they physically spin the motor, like water through a hydroelectric dam. This is also where those ancient Adenine based transporters come into the picture.

Pyruvate is first oxidized and stripped of a carbon (released as CO₂), with NAD+ accepting electrons to form NADH. The remaining 2-carbon fragment immediately attaches to Coenzyme-A (CoA), forming Acetyl-CoA, the universal fuel. Several metabolic pathways converge here. Glucose metabolism runs via pyruvate, but fat, protein, and ketone body metabolism follow slightly different paths to also produce Acetyl-CoA.

The Acetyl-Coa enters the Citric Acid Cycle. This is the core set of reactions where the fuel is fully oxidized to CO2 and more NADH.

NADH now has extra electrons, and it carries them to the mitochondria membrane.

A series of iron-containing protein complexes collectively called the ‘electron-transport chain’ sit in the membrane, and these contain electric pumps. As electrons flow through these machines along the iron wires, the energy is used to pump protons (H⁺) out of the inner compartment.

The proton pumping builds up a ~0.15 volt pressure gradient across the mitochondria inner membrane. The protons really want to get back inside.

Since they can’t get past the force field, their only way in is through the turbine. As they rush in through the turbine they physically spin it so it can slam ADP and Phosphate together into ATP.

You may be wondering why we need oxygen for this at all? Remember that Oxygen is the ultimate end-boss of electron grabbing. At the end of the electron-transport chain Oxygen is waiting to perform the final oxidation. Taking the electrons after they’ve done their work, and combining them with the protons (H+) that have flowed through the turbine to form water. This is why we breathe. Without oxygen to mop up the protons and electrons at the end, the whole system backs up and stops.

Often we learn things about nature by studying what can go wrong. Blocking of this last step in the chain, where oxygen mops up the protons and electrons for the final reaction to water, is the molecular mechanism behind various shitty ways to die. Carbon Monoxide, Cyanide, and a few other poisons block this step, which immediately backs up the entire chain and stops the powerful 1 → 30 ATP power plant. Some cells, like muscle cells, can survive on fermentation (1 → 2 ATP) for a while. But the critical and very ATP hungry heart and brain cells can’t and run out of ATP within minutes.

I still found it not entirely obvious how this whole chain equates to burning methane though, but it becomes clear by taking a moment to zoom out. The fundamental chemistry is no different. It’s just that a lot of stuff happens in between to create a controlled oxidation much faster than rusting iron, but much slower than setting methane on fire:

glucose → mechanically cleaved into 2x Pyruvate

Pyruvate → Acetyl, a simple small carb (−COCH3) not unlike methane (CH4)

Acetyl + O2 → CO2 + H₂O + Heat (but the intermediate steps here both drive and require the intricate electron and protein shuffling machinery which builds ATP)

NAD+/NADH is the key logistics system to handle the electrons, enabling our cells to extract power along their path to get snapped up by oxygen. In its ‘empty form’ as NAD+, it accepts electrons gladly but without violently ripping them off like oxygen would. The ‘reduced’ version NADH is even quite happy to give up those electrons to the Electron Transport Chain. When it does, it turns back into NAD+ and heads back to the furnace to grab another load. Where does the H go? That’s the proton that gets pumped across the membrane and then flows back through ATP Synthase to spin the turbine.

What I find so cool about all this is that it’s simultaneously absurdly intricate, but also quite obvious. We need a wire made from something that conducts electricity (iron) to move electrons. There is a voltage. The voltage enables a turbine to spin. The turbine charges a battery and gives off heat. All of the rules of the game are the same at this nano scale as they are in a man-made powerplant. The biological power supply system is highly decentralized though. We have tens of trillions of mitochondria in our body. it’s also hyper efficient, as this meme shows:

The ‘for example’ part really sets it off for me. For the avoidance of doubt, bodies don’t burn cocaine. Stimulants work by turbocharging our adrenaline system which does then in turn boost our metabolism.

Now what?

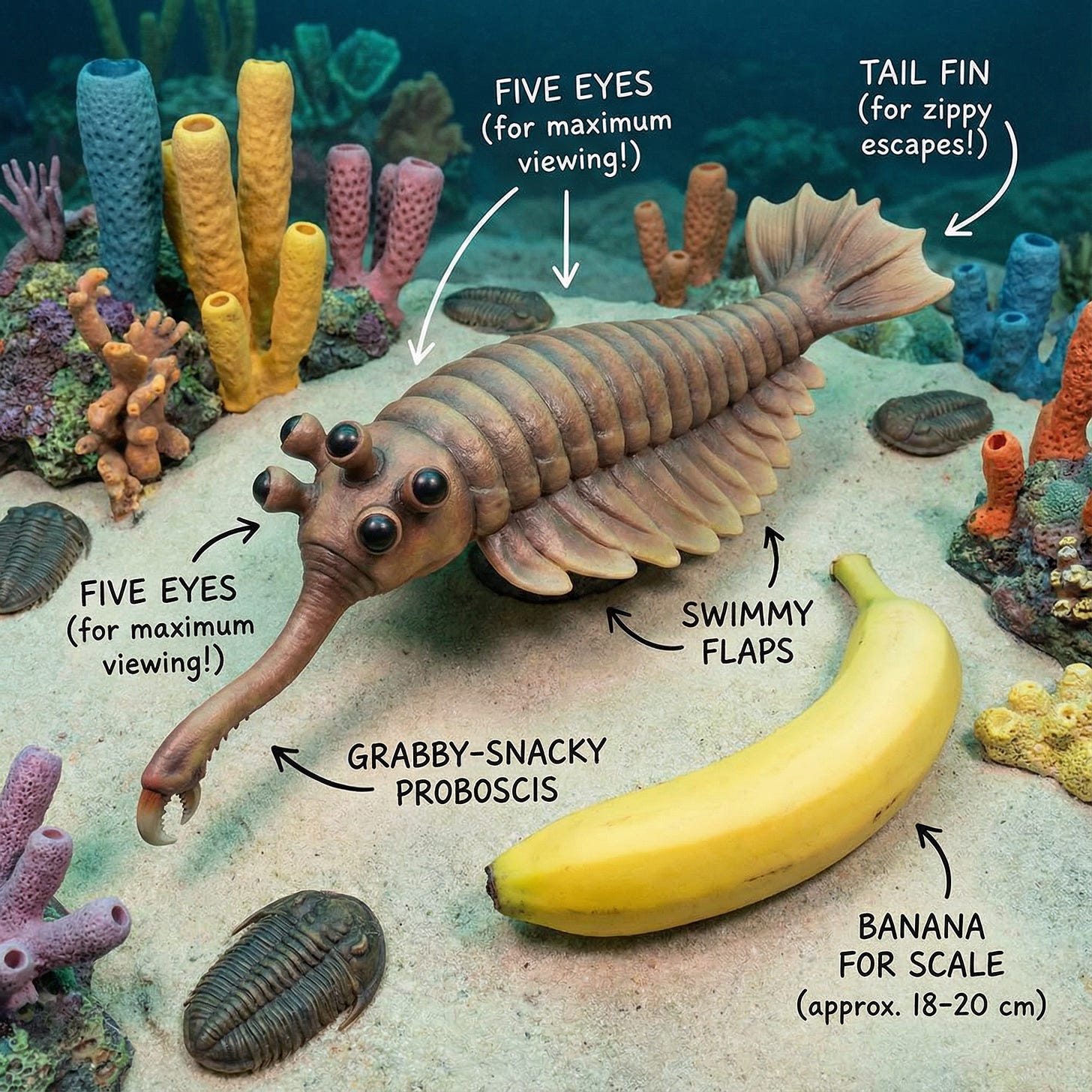

Basically, the whole point of this post was explaining how cool ATP Synthase is, how much of a wonder it is that we exist, and hopefully triggering some philosophical star gazing about life. We’re powered by tiny electromotors spinning at jet engine speeds to charge our batteries with solar power. And not just us. Every living thing on earth: dogs, trees, bacteria, all run on the same ancient machinery invented in the first few billions years of life on earth. It is truly crazy. It’s no wonder that many scientists feel such a sense of awe as they learn more about nature, some even starting to believe in god. I have to admit that the closest I have ever come to believing in ‘something bigger’ was through studying biology. The system is so insane and elegant that it just seems impossible to have appeared by coincidence. But on the other hand, it is a universal truth that a complex system that works, always evolves from a simple system that works. And we surely can go very far back to learn about the simple systems that first worked. Besides, 4 billion years really is a LOT of time. The fact life happened very gradually, gradually and then suddenly also points to evolution. It took 3.4 billion years from the first replicators to the first multicellular organisms, but only about 60 million more to go from there to full blown animals like the iconic Opabinia. Opabinia a is five-eyed creature so bizarre that when scientists first presented its discovery, the audience burst out laughing (the only reason I know about it is that my kids are currently big fans of Opabinia because it’s in a dinosaur book they have).

Once again, clearly, bootstrapping life from a cosmic hotpot under a cyanide sky to turbine powered monsters was the hard step. From there to humans was easier.

Anyway, cosmic musings aside, the next time you’re sweating during a workout, remember that you’re paying the bill to the second law as all your tiny turbines create order out of chaos. You now also know that lots of word choices from biologists are to be taken much more literally than you probably thought: We really do burn calories, mitochondria really are tiny electro-mechanical powerplants. Living beings really are quite machine-like.

If you did get curious to learn more, here are some ideas for questions to ask AI or google:

What happens in various metabolic diseases? In diseases affecting mitochondria, what are the symptoms and mechanisms?

What happens if you run low on food?

How is metabolism different in cancer cells, and how does that help chemotherapy target cancer cells?

Why is fatigue such a common symptom and how is it different from just being tired?

As for me, I am probably done writing about biology for the time being, but I could see myself do one more about DNA and protein synthesis. But to be honest, this one was kind of a heavy lift already. At least now if I end up talking with someone about NMN supplements I have a place to link them to for the fundamentals of metabolism5.

Some combinations of molecules are so high energy and so desperate to undergo a redox reaction that they explode instantly when they touch. Hydrazine (N2H4) and nitrogen tetroxide (N2O4) for example. This would obviously be very bad if it happens in your pocket, but it’s useful for rockets. When NASA sent humans to the moon, they were terrified that the rocket meant to launch the moon lander back up off the moon would fail to ignite, leaving astronauts stranded on the moon. So they used this fuel mixture. You just spray both into the rocket’s combustion chamber and they will ignite. It’s one of the most reliable ways to make a rocket.

While we’re here, fusion is of course an interesting one. You probably know that scientists have been able to run nuclear fusion reactors, but that they barely generate more energy than we have to put in. Fusing four hydrogen atoms to become one helium is a hugely entropy increasing event (releasing a lot of energy), but it also takes a massive amount of energy to make it happen. In stars, gravity and the sheer mass of the star provides that energy.

This is obviously freaking cool, and us humans figured out how to do it as well. The only problem is that it’s not yet quite economical to do so compared with pumping fossil fuels out of the ground. But as the price of solar power continues to drop, this will change and we will be able to produce fuel for airplanes out of thin air as well. Eventually, if we play our cards right we might have to be careful in a 100 years from now that we don’t reduce the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere by too much.

But as a random interesting aside, mitochondria do still retain a small amount of their own DNA (which is one reason we know they were independent once). This mitochondrial DNA is passed down exclusively from mothers.

But maybe this is a good place for one final aside. There is strong evidence that supplementing NMN boosts NAD+, and there is weak evidence that this leads to increased ATP production. Why? We should be able to theorize a bit now. Perhaps it improves efficiency. Theoretically it should be possible to get 38 ATPs out of a glucose, but the body manages only around 30. Maybe NAD+ is a bottleneck here and with more of it the yield increases? Or, we know that the turbines can spin at up to 21k RPM, but in rest, they spin much more slowly. Perhaps rather than making the process more efficient, having more NAD+ just cranks up the speed? Another study seemed to indicate that NAD+ stimulates a pathway that creates new mitochondria, so maybe that’s the mechanism? Or maybe some of all of the above? This translation to reality and intervention is unfortunately always where biology gets more and more muddy.